|

Our Cultural Rug-Pull: Gender Bias

How do we change the subtle short-changing our culture imposes on young female minds?

What is "gender bias?" It deals with differences in how we treat the two genders, differences created by our cultural programming.

In school and at home, the fundamental areas of concern are differences in how we behave toward our boys and girls, differences in what we teach them and what we expect from them.

Bias in schools.

As reported in Oregon Education, research into sex-biased classroom interactions done by Dr. Myra Sadler and her husband, David, found that:

- Teachers pay more attention to boys and spend more time interacting with them than with girls.

- Males receive more praise and more criticism. Feedback to boys is more precise, which means the help they get is more specific and instructive. Girls are more likely to be praised for neatness and promptness, while boys are praised for effort.

- Teachers expect girls to follow rules of classroom behavior and assignments while boys are allowed to bend the rules.

- When tasks are complex, teachers spend more time giving boys detailed directions on how to do the tasks and more encouragement to try harder. Males thus learn how to attack a problem and how to be independent. Teachers are more likely to do the task for girls.

Not all teachers do all of these things, but most of them do some of them, and there doesn't seem to be any difference between male and female teachers. We all get the same cultural programming.

We don't do it on purpose.

A striking example of how unknowingly we practice our bias was shown in a 20/20 television program on the subject to gender bias. When a dedicated, skilled teacher considered the idea that she might be favoring one sex over the other in her teaching, she was certain that, no, she was even-handed with both boys and girls. And then she allowed cameras to perform a reality check.

She, and the viewer, saw her again and again pass over girls to give boys permission to answer a question or to demonstrate a point. You could see the frustration written on girls' faces as boys got the nod again and again.

And then you saw the teacher's shock and chagrin after she saw the video record of her performance. And her resolve to never let it happen again.

That program was an awakening for that teacher, and concern for this issue is rising in Ashland schools, which is perhaps the second place concern should be felt.

Bias begins at home

The first place for concern is at home. How many of us habitually compliment our female children on how pretty they look? Subtext: appearance is the primary factor by which you are judged. Is it any wonder that some girls spend far more time, especially in adolescence, in front of a mirror instead of in front of books. They got the message.

And, rather than appearance, don't we compliment our male children on how well they perform? Which message is the more motivational when it comes to schoolwork?

And how many of us, when dealing with boys and girls together, give the majority of our attention to noisy, boisterous boys?

It's all unconscious, deeply rooted behavior that has little cause to rise to the surface and be visible. But today's teachers are more and more aware.

We talked to two Ashland teachers who spoke on the subject of gender bias at an American Association of University Women panel at SOSC; Jill Joos, a second-grade teacher, and Susan Baird, an eight-grade teacher.

The training in a seminar on "Gender/Ethnic Expectations and Student Achievement" that Ms. Joos attended has sensitized her to her own classroom biases, and this new awareness has helped her shape her teaching with questions such as, "Am I truly paying more attention to the boys? If I do, is it because of what they do, or because of what I do?"

For example, she's found that even a teacher who works hard to meet the needs of each individual child can discover an unconscious bias that has crept into her technique. While she feels that gender bias isn't a factor in her class, she found a "volunteer" partiality in her technique, a tendency to call on those children in the closest row, the eager ones that shot up hands to answer a question.

So reminded, now she makes sure she waits for the slower responders to have a chance to take part. But it isn't always easy to do; like most behavior, there's a real-world reason for this "bias"--time. There's only so much of it, and how much and how long can you wait for the slow ones to get a hand up before you lose the attention and momentum that you've worked hard to create and sustain?

The good thing is, Joos says, that the workshop brought the subject to the top of her mind, and this fresh awareness has helped. And her students benefit.

She came back from the workshop intending to share what she'd absorbed with the rest of the staff, but has yet to do it. Why? Sigh, time. There's so much to do, so many goals to meet. And dealing with gender bias isn't a school goal--yet.

Joos feels that gender bias had an effect on her own life and career. When she was a student she took qualifying tests for a special math and science magnet school, passed all the tests, and then declined the opportunity, choosing instead to follow a more creative path even though she felt she was even stronger in science. Why? Her feeling that, even though she passed the tests in the top five percent, it must somehow be a mistake and that she couldn't maintain that level of achievement. It was a defeatist way of thinking that she feels must have been related to the way society defined female ability in math and science.

Susan Baird says she now knows that when she was a new teacher she was heavily biased toward boys. She credits much of the tilt to being raised with two brothers. It was girl students who finally made her aware of her bias. They asked, "Why do you like the boys better?" At first she denied it but, once called to her attention, the truth made itself felt.

She's worked ever since to avoid bias, and it is work, a constant challenge to keep reminding herself. And she reminded us of how insidious the seeds of bias are when she mentioned the recent hoopla over a talking Barbie doll that whined, "Math class is tough."

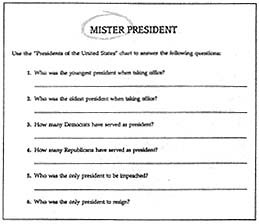

Baird also provided the following example of how bias works in tiny, unseen steps. For what reason is the worksheet to the right titled Mister President? Sure, all of our presidents have been male so far, but this title, in a small way, lets kids know that the job is closed to girls. American presidents are "mister," and it becomes a "fact" when printed in an official, authoritative school document. Baird also provided the following example of how bias works in tiny, unseen steps. For what reason is the worksheet to the right titled Mister President? Sure, all of our presidents have been male so far, but this title, in a small way, lets kids know that the job is closed to girls. American presidents are "mister," and it becomes a "fact" when printed in an official, authoritative school document.

Why didn't the author choose "Presidential Facts" or any of countless other titles? Because he or she, like the creators of all our classroom texts and materials, also operates with what computer lingo refers to as a virus in our programming.

While this is an almost amusing example of what might be called "curricular bias," Karen Dalrymple, executive director of the school district, tells of a more serious example in which the methodology itself is loaded against females.

In fourth and fifth grade, parents and teachers start hearing girls express feelings of inadequacy in math, and at least some of the cause lies with a very subtle bias. According to Dalrymple, girls need a lot of language and discussion to process math, probably more than males. But, by the time children reach fourth grade, emphasis on pencil-and-paper math work grows and there isn't as much of the dialogue and discussion girls need to "get it," and inequity begins.

From her own childhood, Dalrymple recalls being told by a teacher not to ask questions during math lessons because she would interfere with instruction. As she tells the story, undiminished anguish rises up to color her voice.

But, even for an experienced, dedicated teacher, sometimes there are situational factors that generate a male bias. Baird mentioned that sometimes she will call on a boy who's about to explode into "bouncing off the walls" just to keep him focused and on track. And who's to say that's not the right thing to do at that time?

This bias thing is pretty much loaded against girls, but it does work both ways. At the Middle School, for example, there are no boys' volleyball teams. And, until recently, there were no mirrors in the boys' restrooms because, apparently, no one thought boys might be interested in their appearance. It turns out that they are. But these negatives are featherweight compared to the burden bias places on girls.

What to do?

Since the bias bears most negatively on girls, parents of girls can begin watching for their own biased behavior. The next time an "appearance" compliment for a girl rises to the parents' lips, they should hold it until it can be connected to or replaced by a compliment on some other virtue--with, intelligence, performance, integrity, social skills, etc.

Another key thing to do, for all kids but especially girls, is to reinforce girls in their ability to solve problems by themselves, an ability they have in as full a measure as males.

In addition, not that they need anything more on their dance card, maybe our school district can formulate a brief program to be used in staff meetings to raise the awareness of teachers to their own possible biases, and to give them tools with which to avoid it. Jill Joos feels certain that teachers can improve equity by focusing on specific teaching strategies and practices. The tools can be remarkably simple, such as the notion we heard from elementary teacher Peg Pauck: just make sure you alternate girl-boy-girl when choosing kids to respond. If, that is, you are sufficiently sensitized to the problem to make it possible for you to remember to do it.

Gender bias isn't the only one to affect teachers and parents, but it is one that has a lifelong effect on our children. The good news is that teachers like Joos and Baird are two among many who work at creating a new bias against bias.

|